It easier to teach something you have experienced firsthand. This is why teachers’ learning should reflect the ways we wish their students to learn. Instruction is situated in one’s own experiences.

I am not talking about activities in professional development, but those same elements that provide deeper learning experiences for students in classroom:

- focusing on transferable understanding,

- providing opportunities to reflect,

- relating new information to previous knowledge, and

- bridging theory with practice.

Truly focusing on life-long learning.

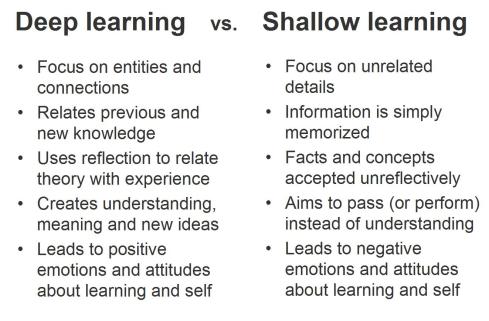

Teachers as learning professionals still need occasional reminders about how to support their own learning process, because in the professional world the expectations for showing competence by generating learning products (evidence, projects, artifacts, exams, etc.) sometimes take over the deep learning process, and thinking about how learning really happens, and how it can be supported on personal level. Knowledge of metacognitive skills is an essential tool for anyone who wants to teach.

Metacognitive awareness includes the knowledge and perceptions we have about ourselves, understanding the requirements and processes of completing learning tasks, and knowledge of strategies that can be used for learning. Teaching metacognitive knowledge and skills is an important part of supporting deep learning. We as teachers should have extensive knowledge and skill to embed metacognitive strategies into our everyday practices.

Just like classroom learning experiences, also teacher learning should be designed to support self-regulated learning (SRL) practices. SRL refers to students’ cognitive-constructive skills and empowering independent learning, focusing on strengthening the thoughts, feelings and actions that are used to reach personal goals (Zimmerman, 2000). This approach aligns well with the research of adult learning, which highlights the use of constructive-developmental theories (e.g. Mezirow, 2000; Jarvis, 2009; Stewart & Wolodko, 2016).

Supporting students’ SRL becomes easier to embed into instruction when we have first practiced in our own learning. This cannot be achieved by following a script or curriculum book, but situating the knowledge of pedagogy in classroom practice.

Using SRL as a chosen approach in professional development or other learning opportunities helps to recognize our own fundamental beliefs about learning. These beliefs, that either help or hurt learning process, are always present in both teaching and learning situations.

Following the three steps of SRL helps us to approach learning tasks within their context, and first create a functional plan and choose learning strategies to support learning process. Then, we will want to monitor our own performance and learning process during the second part, performance phase. This is where the knowledge of deep learning strategies is very important, because sometimes instruction and design reward surface processes, and we might want to change our strategies to still engage in deep learning. In the third phase, self-reflection, is the most important one, but often forgotten. Without engaging in self-assessment about our own learning process, it would be hard to do things differently next time, if needed. Yet, the whole idea of using metacognitive knowledge to improve deep learning relies in dealing with our own perception and managing our emotional responses, so that our beliefs about deep learning are strengthened. Some beliefs are detrimental for deep learning, and for example mentally punishing ourselves (for failure, procrastination, etc.) leads toward using surface learning processes.

Instructional approaches that emphasize choice, learning ownership, knowledge construction, and making connections are more likely to facilitate deep learning and understanding – for teachers and students alike.

Here is more information about SRL for adult online learners in a PDF form.

Jarvis, P. (2009). Learning to be a person in society. In K. Illeris (Ed.) Contemporary theories of learning: learning theorists… in their own words. London: Routledge.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Stewart, C., & Wolodko, B. (2016). University Educator Mindsets: How Might Adult Constructive‐Developmental Theory Support Design of Adaptive Learning?. Mind, Brain, and Education, 10(4), 247-255.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulated learning: a social-cognitive

perspective, in M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (Eds.) Handbook of Self-regulation (pp. 13–39). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.