My last blog post was about the importance of reflection, and how it is the best tool for anyone who wants to teach. I try to take my own advice and engage in reflection during my workdays. Supporting adult students’ learning is sometimes harder than supporting the learning of younger students. As adults we have stronger preconceptions about our learning abilities and preferences, based on the previous educational experiences. Sometimes these unwritten rules make effective learning harder.

Today I red about an amazing book and found their website: Contextual Wellbeing is such an important concept for education today! Focusing on important (instead of urgent) improves the outcomes of most processes. Learning process is no exception of this rule. Shifting focus from competitive educational model to equitable educational communities that emphasize contextual wellbeing is the challenge.

Making education better requires a systematic change, and changing focus from learning products to learning process. However, we all can make small changes in our own instructional settings and improve the learning experiences our students have. My common request for my students is that they pay forward the learner-centered education with non-punitive assessment system they have experienced. It is much harder to to change to learning- and learner-centered education if you have not experienced it. We all tend to instruct in the way we were instructed, unless we reflect on our dispositions and practices. Yet, as teachers and faculty we all can take small steps towards this direction by focusing on supporting learners autonomy, relatedness and copetency.

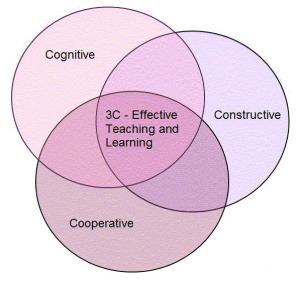

Supporting adult learners includes the same components of respect and compassion as all other teaching, and builds similarly on 3Cs: The cognitive learning approach combined with constructive and cooperative practices that enable effective teaching and meaningful learning.

C1 – Cognitive approach makes supporting adults’ learning easy and effective. Viewing learning as a student-centered and dynamic process where learners are active participants, it strives to understand the reasons behind behavioral patterns. Discussing values and mental models is the first step. Talking about forethought, performance control, and self-reflection helps students to improve their academic performance by learning how to self-regulate their behavior, engagement and learning. Having conversations about the hierarchy of concepts in learning material and providing support to create graphic organizes and mental models is an important part of the learning support. Establishing and resetting process goals and completion goals, as well as discussing conditional goal setting is important!

C2 – Constructive practice emphasizes the learning process and students’ need to construct their own understanding. Interactions are the basic fabric of learning! Delivered or transmitted knowledge does not have the same emotional and intellectual value. New learning depends on prior understanding and is interpreted in the context of current understanding, not first as isolated information that is later related to existing knowledge. Constructive learning helps students to understand their own learning process and self-regulate and co-regulate their learning in the classroom and beyond. Regular feedback, self-reflection and joint reflection with respect and compassion are important! Teachers’ strong pedagogical content knowledge is a prerequisite for successful constructive practice.

C3 – Cooperative learning is about holistic engagement in the learning process. The guiding principle is to have learning-centered orientation in instruction and support. Students learn from each other and engage in collaborative meaning-making. Every student has their own strengths and areas to grow, and growth mindset is openly discussed in class. Teaching and learning become meaningful for both teacher and students, because there is no need for the power struggle when interactions are based on respect and compassion. From students’ perspective cooperative learning is about respecting the views of others and behaving responsibly while being accountable for your own learning. At best this leads to learning enjoyment, which is a prerequisite for life-long learning: why would we keep on doing something we don’t like? In 21st Century nobody can afford to stop learning.

The discussions I have with my grad students are amazing. Every day I talk with teachers who have so much passion for their work, so strong dedication for making learning better for their students, and such a drive to gain more professional knowledge. I am privileged to support my students’ learning process by engaging in dialogue with them. Of course, there are also teachers whose goal is just to pass their courses and earn their degree by demonstrating their existing competencies, and the dialogue with these students is different. As a faculty member I respect their strategic learning approach, but also offer opportunities to engage in deeper learning discussions and support their learning process and wellbeing.

The best tool I have found for supporting adult students’ learning process and contextual wellbeing is open and honest communication. I try to open the dialogue by listening what my students are thinking, and expanding their knowledge of curriculum, instruction and research by communicative interactions. This is what I think pedagogy and andragogy are really about: supporting students’ deeper learning in dialogue.